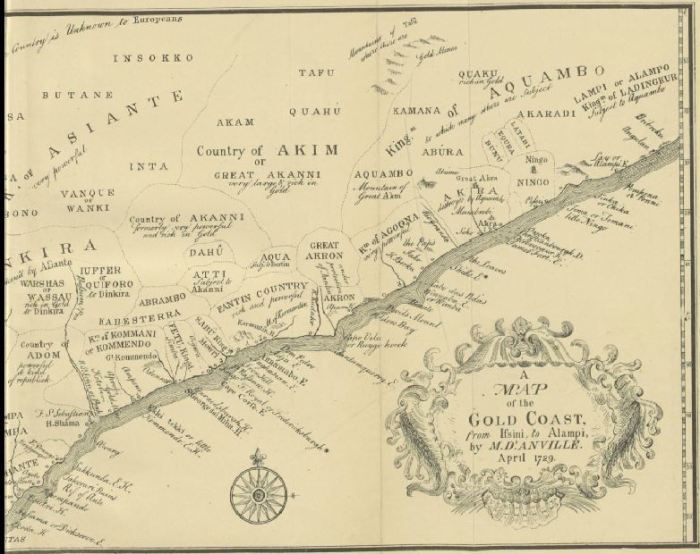

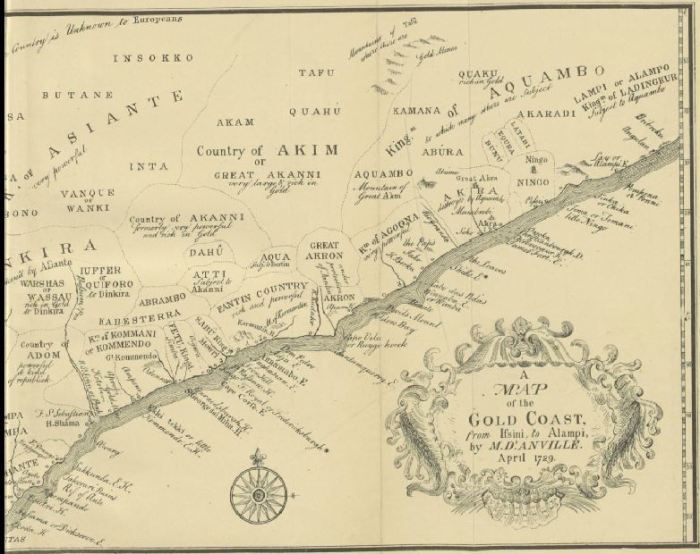

In 1750, An act for extending and improving the trade to Africa, incorporated the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa as a non-profit regulated company to “facilitate Britain’s African trade” by governing and maintaining a series of trading establishments on the African coast.[1] The purpose of the company was to protect free trade, a role the state would later adopt. The CMTA replaced the bankrupt Royal African Company. Regulated companies differed from joint-stock companies in that members of regulated companies did not participate communally to enhance the price and thus wealth of stockholders.[2] The company did not sell shares, nor cold coastal employees partake in the slave trade for their own personal gain. Private merchants paid the CMTA 40 shillings a year for the use of the forts on the African coast. Parliament provided most of the company’s finances through an annual stipend. The main purpose of the company was to protect free trade and avoid competition between the company and private merchants. According to historian Christopher Brown, in The British Government and “the Slave Trade: Early Parliamentary Enquiries, 1713-83,” the 1750 Act “aimed to resolve the long-standing tension between a joint stock corporation that had long since lost its commercial standing and the individual traders who conducted the commerce, but had no institutional recognition.”[3] The CMTA was an attempt to synthesize corporatism with free trade, debates surrounding the company reveal insight into the changing roles and relationships between the state, corporations, and private merchants during Britain’s expansion as the prominent commercial Empire.

CMTA archives provide scholars with indispensible information on a breadth of topics ranging from the regulations of trade to relations between company employees and African communities on the coast—especially the Fante. Despite a wealth of scholarship published about these relations, scholars sometimes confuse the CMTA with the Royal African Company, but these were two distinct companies. For instance, historians Randy Sparks and Rebecca Shumway refer to the CMTA as the Royal African Company. Part of the reason for this confusion stems from title of the archives. One of the main sources for insight into life on the African coast comes from the treasury records (T 70) of both companies. Unfortunately the title of the series holding both the Royal African Company and the CMTA’s records are titled: Company of Royal Adventurers of England Trading with Africa and successors.[4] Eveline Martin’s “The English Establishments on the Gold Coast in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century,” provides a detailed study of the companies constitution and provides further sources for reading about the company.[5]

The company consisted of a governing Committee, in England, and Council of governors on the coast lead by the Governor of Cape Coast Castle. Nine men ran the Committee; three men were elected from each of England’s main slave port cities—Bristol, Liverpool, and London. According to Martin, “the functions of this Committee bear no comparison with the powers possessed by the Directors of the Joint-Stock Companies.”[6] Their main function, Martin argues, was to obtain the annual stipend from Parliament and use it to purchase the necessary supplies for the coastal staff. Although the company was independent from the state, the Board of Trade oversaw complaints leveled at the CMTA when they occurred and even launched several investigations.[7] On the coast, the acting Governor of Cape Coast Castle led a council of officers, as mentioned above. The forts were organized in a hierarchical fashion, when officers moved up in rank, they would move to the next fort in the hierarchy.

Several excerpts from the 1750 Act help explain the role and intentions for creating the company. For instance, “It shall not be lawful for the Company established by this Act, to trade to or from Africa in their corporate or joint Capacity, or to have any joint or transferrable Stock, or to borrow or take up any Sum or Sums of Money on their Common Seal.”13 Section XXIV reads, “no Officer or any other Persons to be employed by the said Committee… at any Time hereafter, in any Manner, or on any Pretence, obstruct or hinder any of his Majesty’s Subjects in Trading and that the Forts.”14 Section XXVI and XXVII state that the Warehouses, and Buildings, already erected, or which shall hereafter be erected, by the said Company, shall be applied and appropriated wholly to the Maintenance, support, and Improvement of the Forts and Settlements already” and that the forts and other buildings “shall be free and open to all his Majesty’s Subjects.”15 The Act prohibited officers from trading for profit or hindering the trade of British merchants and stated that the forts were to be kept open for private merchants. Officers, however, violated each of these measures.

The CMTA had three major tasks. First, company employees were supposed to maintain the to assist private merchants and help expedite slaving voyages. Company officers, or chiefs, were supposed to assist merchants by keeping the forts supplied with slaves to sell private merchants.[8] Secondly, the forts acted as important signs of possession to deter European rivals from establishing trade on the coast. This meant that the forts were supposed to have working armaments. Chiefs were also supposed to raise the British flag to help as a deterrent. Thirdly, company officers were to maintain friendly open relations with the local African communities. This involved paying rent, giving presents (dashees), participating in local courts (palavars), and complying with other Fante norms. The British established themselves on the coast at the invitation of African merchants and the Fante made sure the company knew that they [the Fante] were in charge.[9]

Payment of coastal officers created problems for the company and prevented officers from fulfilling the three main goals of the CMTA mentioned above. Private merchants accused officers of trading slaves for their own private profit. Joint-stock advocates accused chiefs of neglecting their duties, by letting the forts fall apart, thereby endangering the trade against European rivals.

Europeans and Africans on the Gold Coast traded in goods not species. The Governing Committee, in England, provided coastal employees with goods, which they were supposed to trade for slaves. Which goods the Committee sent depended on Fante demand, but there was often a lag between when the goods were purchased, sent, and the changing demand of the Fante. This meant that employees often received goods that were out-of-fashion. To make matters worse, employees were also paid in tradable goods. To keep the forts filled with slaves, the forts had to be supplied with enough goods that were in high demand on the coast or else the forts would not be able to purchase slaves from the local community. The Committee, also, paid the officers in goods, which they were supposed to trade with the Fante for their income. Thee Fante did not depend on Europeans for subsistence economy, they traded with Europeans for luxury (or non essential items), if a certain good went out of fashion, company officers were in trouble. Officers found that it was easier to trade slaves using company stores. Although some officers greatly benefited—such as Richard Brew—others traded merely to survive—Philip Quaque. Either way, officers spent much of their time trading for their own sustenance or livelihoods, which lead to competition with private merchants.

The extensive complaints against the company created debates in England about the role and merits of free trade, joint-stock trade, and the government’s responsibility in a commercial Empire. As mentioned above, the complaints were often leveled at company officers. In the public sphere, contemporaries did not take into account the effects of the Fante on the company or the overall mismanagement of supplies. Historians, until recently, also overlooked the power of the Fante on the coast and the effects of their dominance on political debates involving the CMTA in England. For instance, when slave prices rose, new goods were needed, and payments to the Fante increased for various reasons, the Committee would have to ask for more money from Parliament, which lead to heated debate over the company and the conduct of its employees on the coast. These debates raised questions about who and how to govern and protect the Empire’s trade–joint-stock companies? Regulated companies? The state? In other words, a transnational study of the CMTA from 1750 to 1777 should provide insight about how cross-cultural interactions affected English politics.[10]

The following is a list of works about cross-cultural relations on the African Gold Coast involving the CMTA

Martin, Eveline Christiana. “The English Establishments on the Gold Coast in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century,.”5 (1922)

Reese, Ty M. ” Eating” Luxury: Fante Middlemen, British Goods, and Changing Dependencies on the Gold Coast, 1750-1821.” The William and Mary Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2009): 851-872.

———. “An Economic Middle Ground?: Anglo/African Interaction, Cooperation and Competition at Cape Coast Castle in the Late Eighteenth Century Atlantic World.” Interactions: Regional Studies, Global Processes, and Historical Analysis

———. “‘Sheep in the Jaws of So Many Ravenous Wolves’: The Slave Trade and Anglican Missionary Activity at Cape Coast Castle, 1752-1816.” Journal of religion in Africa 34, no. 3 (2004): 348-372.

———. “We Must Keep Black Men of Power in Our Pay: The Reliance of the English Slave Trade on African Labor.” Proceedings of the Ohio Academy of History (1999): 51-62.

Reese, Ty M.. “Controlling the Company: The Structures of Fante-British Relations on the Gold Coast, 1750–1821.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 41, no. 1 (2013): doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.762162.

———. “Facilitating the Slave Trade: Company Slaves at Cape Coast Castle, 1750–1807.” Slavery & Abolition 31, no. 3 (2010): doi:10.1080/0144039x.2010.504538.

Shumway, Rebecca. The Fante and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Boydell & Brewer, 2014.

Sparks, Randy J. Where the Negroes Are Masters. Harvard University Press,

[1] Eveline C. Martin, “The English Establishments on the Gold Coast in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 5 (January 1, 1922): 167–208; Ty M. Reese, “Facilitating the Slave Trade: Company Slaves at Cape Coast Castle, 1750-1807,” Slavery & Abolition 31, no. 3 (September 2010): 363. The forts and other settlements under the companies jurisdiction lied “between the Port of Sallee in South Barbary, and the Cape of Good Hope,” see: Geo. II. c. 31. See: Donnan, Elizabeth. Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America. The Eighteenth Century Volume II Volume II. 1931, 474ff.

[2] Leonard W. Hein, “The British Business Company: Its Origins and Its Control,” The University of Toronto Law Journal 15, no. 1 (January 1, 1963): 144, doi:10.2307/824910; M. Schmitthoff, “The Origin of the Joint-Stock Company,” The University of Toronto Law Journal 3, no. 1 (January 1, 1939): 77, 79, 80, 81, 92, 94, 95,

[3] Christopher Leslie Brown, “The British Government and the Slave Trade: Early Parliamentary Enquiries, 1713-83,” Parliamentary History 26, no. 4 (2007): 27.

[4] For more information on the classification of African Companies, please see: Jenkinson, Hilary. “The Records of the English African Companies,.”6 (1912).

[5] Martin, Eveline Christiana. “The English Establishments on the Gold Coast in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century,.”5 (1922)

[6] Martin, Eveline Christiana. “The English Establishments on the Gold Coast in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century,.”5 (1922), 172.

[7] Ibid., 174.

[8] Slaving voyages were funded by plantation owners and other merchants, they set a quota for the amount of slaves they wanted to purchase. Someties, the slave ship captain would coast up and down the shore until he purchased enough slaves to fill the quota. Coasting could take weeks or months, during which time, captains would have to purchase provisions for the crew and slaves they already had on board. The settlements were meant to help expedite the voyages. A chief was supposed to keep the fort “stocked” with slaves using goods provided by the governing Committee in England, who received finances from Parliament.

[9] Ty M. Reese, “Controlling the Company: The Structures of Fante-British Relations on the Gold Coast, 1750–1821,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 41, no. 1 (2013): 105, doi:10.1080/03086534.2013.762162.

[10] Global Determinants of the English Constitution